[This is part two in a series of posts on probability and roleplaying games. You can begin with part 1 here.]

RPG designers haven’t always looked at the role of probability in action-taking in the same way. In fact, over time, those designers have made it more and more likely that players will succeed at their actions.

What’s the most common thing players do in RPGs? They try to whack a baddie on the head. So let’s start from there and see how likely, historically, you’ve been to successfully whack that baddie. And let’s narrow it further and look at fantasy RPGs: what happens when a fighter-type tries to smack a goblin with a sword? How often does he hit?

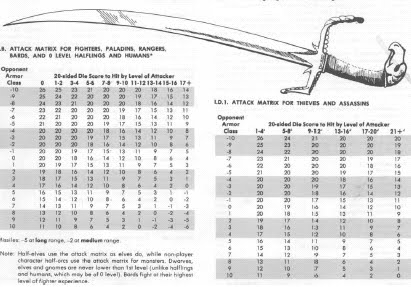

If we jump in the Wayback Machine and head to the days of 1st Edition Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, said fighter’s chances ain’t looking so good. A 1st-level human fighter with Strength 16 – average for a fighter using the recommended method for rolling character attributes – has only a 30% chance of hitting a lowly goblin with his sword. That’s right: just 30%. Now, there were a lot of quirks to AD&D’s system are worth exploring in their own right, as they show other ways in which the genre has evolved; for example, all 1st-level characters had exactly the same chance to hit our poor goblin, but fighters were vastly more effective at higher levels, which is very different from how most modern games handle level progression. Still, for now, we’ll just stick with our simple number.

In other words, back then, a character could be expected to fail at this core action over and over. Fast forward to AD&D’s 3rd Edition, and the picture looks somewhat different. Take the 1st-level human fighter again, still with Strength 16. He’s got +4 to hit – +1 from having a level of fighter, +3 more from Strength – and he’s facing a goblin with an AC of 15. This gives him exactly a 50% chance to hit.

Now look at the 1st-level human fighter of today. He has a Strength of 18 if we use the standard score array and assign his +2 racial bonus to Strength. This gives him +4 to hit from his strength, +3 more from using a long sword. We presume he chose the one-handed combat style, for +1 more. We assume no other bonuses from feats, and that he’s just using his basic attack, instead of a power like Sure Strike. There’s not just a single goblin for him to face, but most goblins have an AC of 16. Now he has a 65% chance to hit.

What we see in these numbers is a direct and dramatic climb in the chances of success over the years. This change can’t have been accidental: just take a look at the notes on variant rules in the 3rd Edition Dungeon Masters Guide to understand how sensitive the D&D game design team was to the impact of much more minor rules changes than than these. The designers made a conscious decision to have players succeed more and more often at their actions.

Okay then: why has the number changed so much over time? I think there are four interrelated answers:

- Success is fun. While letting players succeed with their characters’ actions all the time takes away the benefits of dice-rolling, players will nevertheless have more fun if they succeed more often than they fail.

- Inaction is boring. Failure usually results in nothing happening; a miss in combat, or a failed skill check, is usually wasted time.

- Wasting limited resources feels frustrating. If I can only cast a certain number of spells each combat, or can only use my special power twice per day, I’m going to save it up for when it matters; when the time comes, I want it to be likely to count for something. (You can see 4th Edition D&D take this a step further by introducing a number of daily powers that are guaranteed to have at least some effect, albeit a reduced one, even if they fail.)

- Failing takes time. Assuming that the rate of foe failure is similar to that of characters (not always true, but close enough), introducing more failures means that the time it takes to resolve a conflict in a game is directly lengthened by the chance of failure, without changing the eventual outcome.

Now, you can have too much of a good thing. The previous post already explored a bit of why succeeding all the time isn’t necessarily good. Consider also what happens if the time allotted to a conflict is compressed by a very high rate of success: that leaves fewer opportunities for player decisions, fewer chances for tactics and dramatic roleplaying, fewer moments where a gamemaster or computer can spring a surprise on the players.

But the point is that the people in the know – the Dungeons & Dragons designers, reacting to ever increasing amounts of data – steadily hiked up the chance of success, because they saw reasons such changes would improve their game.

Now, another factor started to appear in the ’80s, and has proceeded to become ever more significant, which is the rise of computer RPGs – games which began as followers in the trends set by paper and pencil RPGs, but have since switched roles to become leaders. More on the impact of CRPGs, and the evolution of Conclave’s own use of probability to decide the results of actions, in the next post.