The final portrait, in full painted glory.

(This is the third and final installment of the “art process” series, looking at the development of the first art for Bastion. If you haven’t yet seen them, you might first want to read part 1 and part 2.)

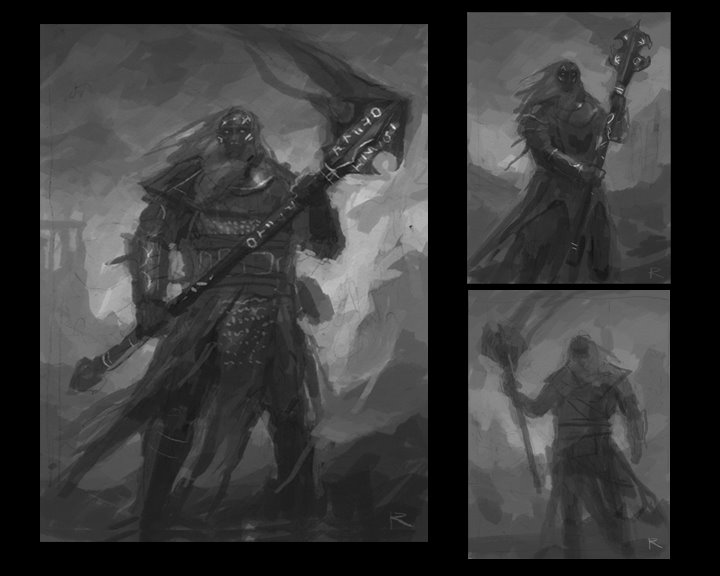

Once we saw the drawing for the Forgeborn, we knew we were in very, very good shape. He was looking nice and broad in the shoulders now, barrel-chested and buff. It was clearer what the look of the runes would be in the final painting. The ruins were clearly present in the background. And we could also see his rune-pouch more clearly. Chris had responded to each of our topics.

My only concern at this stage was whether we were too close to classic D&D dwarf territory. This is something we have to watch with all our art, as well as our character races, our monsters, our skills and abilities… almost everything in the game has to find a sweet spot between looking like Dungeons & Dragons (or Lord of the Rings, or World of Warcraft – the other two major cultural touchpoints for fantasy narrative and gaming), and simply feeling alien to players. Different parts of the game handle this issue in different ways; in the case of the portrait art, and our concepts for the core races, it led us to develop races that are new and unique, but are clearly humanoid and share some characteristics with more common fantasy archetypes. We also made sure to have races and images that are likely to appeal to a variety of different types of players: the Forgeborn are great if you want to play somebody who looks solid and menacing, while those looking for a prettier face might pick a Lumyn, Nix, or Trow.

So, was our dude too dwarfy? Was the beard a bad idea? Derek and Justin said that no, the beard was not pushing the portrait into dwarfland – that once we had color, all would be well. So we simply asked Chris to go ahead and turn the drawing into a final painting.

It didn’t take him long, but we still had to wait around a few extra days before actually seeing the final result. This was because the process of photographing the art is apparently fairly laborious, and Chris was hoping he could save some time by photographing both the Forgeborn and Lumyn paintings together… which meant the Lumyn painting had to be completed as well.

Now, the process of getting the Lumyn ready for prime-time was pretty different. Truth be told, we didn’t have to provide much feedback on the Forgeborn to get him from sketch to final painting; if you compare the big sketch with the final product, not much has changed. Most of our work came in putting together the initial description of the art.

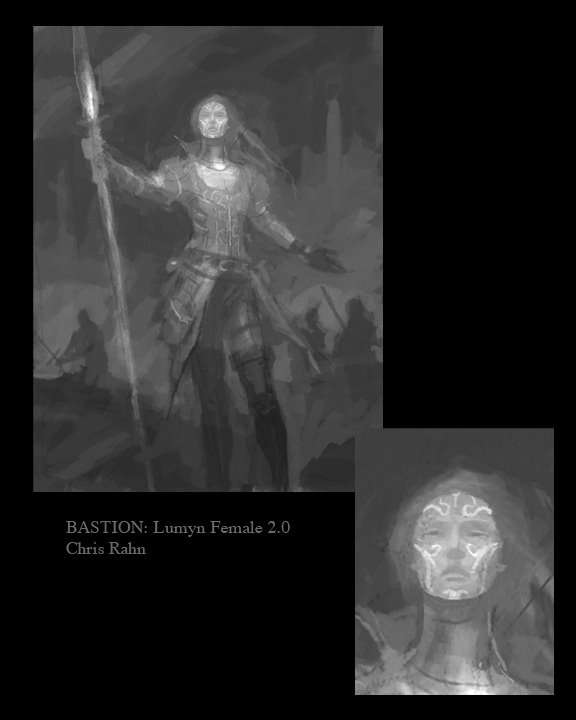

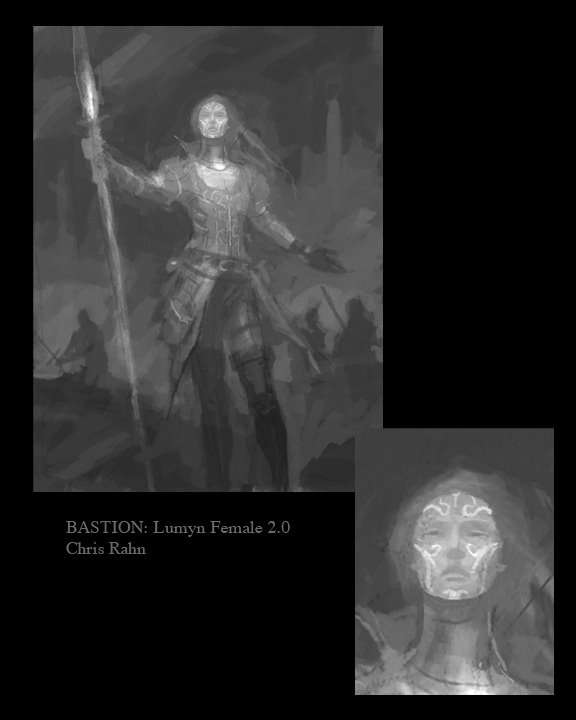

With the Lumyn, it was quite a different situation. We asked Chris to come up with a character who showed qualities of leadership, as well as alchemy. The result was not quite what we anticipated. I’ll put the first Lumyn sketches up again here:

When we saw this, we all realized that “leadership” had not been a specific enough term. We were thinking of battle leadership: somebody who can direct tactics, calculate odds, and rally the troops. What Chris had sketched was a different kind of leader: something like a senator, a demagogue; someone who could lead in the city itself. This poor Lumyn looked like she might break if she ever went on a wilderness adventure!

Before going back to Chris, we worked a lot to better describe our needs for the portrait. For the first time, we offered up a specific visual cue, going through the archives of Magic artwork in search of a character that really showed off the leadership pose we were looking for, and eventually settling on this:

Here, we see a figure who is attractive, but strong; somebody headed forward into the forest, but looking back, either to consider, or to the (unseen) people who are following her. It’s a good portrait pose: you can see much of the body, and also get a great shot of the face.

It felt a little odd to be putting an image in front of Chris: was this a good idea from an artistic direction standpoint? Would it seem too constraining to Chris, or limit his imagination? But we went ahead and did it, because we knew how important it was to get this pose right. We then also asked him to move the Lumyn to a wilderness setting, asked him to emphasize heroism and action, and also asked him to put in more of a sense of her as alchemist – another problem with the original sketch, but less important (as we could always put alchemy in a different portrait if it wasn’t going to fit here).

Chris was very nice about all the changes we were asking for, and quickly produced a new sketch that was much, much closer to what we needed:

Didn’t he nail it? The pose, the practical-yet-elegant clothing, the setting, the other party members in the background, being beckoned… well, we felt pretty good at this stage. There were still a few tweaks: wanting to see that the markings on her face appear throughout here body, and therefore needing some skin to show up elsewhere; making sure the markings didn’t seem to be tattoos; trying to get more alchemy in. With that feedback, Chris produced this drawing:

Yup. Our only feedback was that the head looked a little small proportionate to her neck; Chris agreed, noting that he’d been trying to emphasize the elongated bodies of the Lumyn, but that the gorget then made things look odd.

And so finally we come to the end result: our two portraits, complete:

And that’s that. We were very happy with the end result, as well as the process itself, and now Chris is hard at work finalizing the next two portraits, which you’ll see soon in our new gallery.